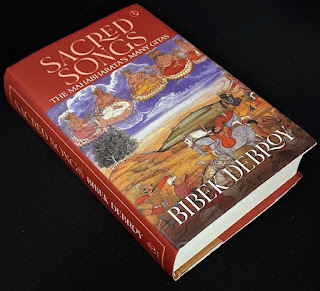

Sacred Songs: The Mahabharata's Many Gitas, by Bibek Debroy

The Mahabharata, given its encyclopaedic length, unsurprisingly, contains many, many Gitas (songs). Surprisingly though, not many people are aware of the presence of Gitas other than the Bhagwat Gita in the Mahabharata. This book is a selection of 25 Gitas from the Mahabharata, with the Sanskrit verses in Devanagri script, along with their English translation.

Gita means song. When one mentions the word ‘Gita’ in the context of the Mahabharata, one is invariably referring to the Bhagwat Gita—Krishna’s divine message to Arjuna on the eve of the great battle between the Kauravas and Pandavas in Kurukshetra. However, there are other passages that are also called ‘Gita’. Taken across the Mahabharata, Ramayana, and Puranas, these number over fifty. In this book, Bibek Debroy has selected twenty-five such Gitas, excluding the Bhagwat Gita, from the Mahabharata.

An obvious question that arises is—what is the criteria for classifying a Gita? In the book’s Introduction, several criteria are listed. One is to take only those that are explicitly called out as such in the Critical Edition of the Mahabharata; only nine qualify. Categorizing expositions and conversations that further an understanding of the purushaarthas (dharma, artha, kaama, moksha) are a more acceptable criterion. This brings the list up to twenty-two. Add the Yaksha Prashna and Sanatsujata and you get twenty-four. The twenty-fifth is the Pandava (or Prapanna) Gita, added on admittedly weaker grounds.